STEM Takes Root in Chicago

Creating the next wave of STEM teachers in Chicago

Creating the next wave of STEM teachers in Chicago

Convincing high school and college students to consider a career in science, technology, engineering, or math (STEM) is getting easier. Convincing them to think about teaching STEM as a top career pick is still an uphill climb. Teenagers participating in the Chicago Public Schools Student Science Fair know that their skills are in high demand.

“To me, STEM means that you can get a job in science, technology, engineering, or math — whichever one fascinates you the most.” said fifteen-year-old Daniel Puczko, an aspiring orthopedic surgeon.

Sixteen-year-old Emily Nash said she will not rule out teaching. “In college, I want to major in agricultural business or engineering, but depending on my pathway, agricultural education could be interesting.”

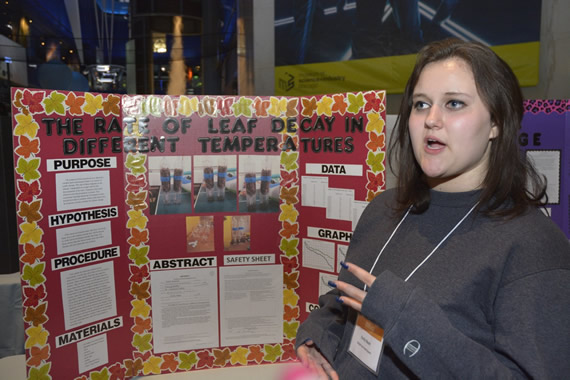

Emily was among the students presenting their projects at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry during a national summit organized by 100Kin10 — short for 100,000 STEM teachers in 10 years, a campaign started by Carnegie Corporation of New York. The nonprofit created a network of organizations that are grappling with an urgent issue for K-12 schools: recruiting, training, and retaining highly-qualified STEM teachers. Their goal is to form a pipeline of candidates at a time when the supply is outmatched by the demand coming from almost every sector of the economy.

“I hope young people see the value of having teachers who inspire them to study in the STEM fields — they often don’t reflect on this until much later,” said Carnegie Corporation’s LaVerne Srinivasan, Vice President, National Program, and Director of the Education Program. “If we can help students realize this sooner, perhaps they will want to become STEM teachers themselves.”

Today 100Kin10 works with more than 200 partners including education nonprofits; foundations; local, state, and federal agencies; teacher associations; colleges of education; and universities. Their conference featured back-to-back brainstorming sessions on challenges like funding, technical assistance, and the need for collaboration. In the area of recruitment, discussions focused on one of the most intractable issues — the lack of diversity among aspiring STEM teachers.

The general consensus is that schools must do more to expose students to STEM, but many districts lack resources and expertise. This is where the 100Kin10 network steps in.

For example, the The Colorado Education Initiative (CEI) works with the state’s education department to assist high-need districts such as the ones serving Native Americans in the southwest section of Colorado.

The nonprofit helps high schools develop strong STEM education programs so that students will graduate STEM ready and qualified for enrollment at a college in nearby Durango, where tuition has been waived for indigenous students.

“By bringing Fort Lewis College into the high schools, we can get students excited about becoming educators,” said Gregory Hessee, a director with CEI. “The goal is to create a pipeline of indigenous undergraduate students in the college, one third of whom will go back into their communities as teachers.”

Teach for America (TFA) finds that computer science is one of the best on-ramps for technology careers, so it is developing a high school curriculum for teachers that will roll out in ten regions during the next three years.

As the head of TFA’s STEM Initiative, Joseph Wilson explained, “Equity and inclusion are at the heart of the curriculum, and the goal is to increase the number of students of color and especially female students of color into computer science at an early age.”

The other half of the 100Kin10 challenge is training and retaining teachers who are already in America’s classroom. Many struggle to keep up with the rapidly changing requirements of teaching STEM subjects in terms of new content, pedagogical methods, and standards for what students must learn.

This is especially true in states like Illinois, which has adopted Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) for kindergarten through twelfth grade. Chicago elementary school teacher Erika Francis has a master’s degree in science education but does not feel prepared to teach to the new standards.

“I need professional development and training as to how the standards should look in my classroom,” said Erika. “I am concerned that our school and our state don’t have the money to properly train teachers to implement the science standards.”

The Museum of Science and Industry (MSI) recognizes the need for more effective teacher training and has become a model for the partnership role that museums and universities can play with local school districts. In addition to programs for students, since 2006 MSI has provided free science education to middle school teachers from high-need schools in greater Chicago.

With support from Carnegie Corporation, MSI recently launched a Science Leadership Initiative. Highly-motivated teachers take what they have learned at MSI back to their schools, where they serve as science ambassadors for a three-year process aimed at promoting better science education throughout the school.

“Whole school change involves getting the teacher leader, administrators, and other teachers to ask where are they now, where can they go, and how can they establish a culture for science in their school,” said Nicole Kowrach, MSI’s Director of Teaching and Learning, adding that there are built-in benefits for retention. “We believe that this kind of opportunity will keep a really good teacher in the classroom.”

As a teacher in the new program, Laura Gluckman is working to transform the way science is taught at her elementary school.

“Because I had so little science background, I relied a bit on the textbook — science as reading then a separate lab,” said Gluckman. “MSI helped me learn hands-on approaches, scientific practices, inquiry-based learning, and how to teach children to ask a question, then find and explain their evidence.”

This relationship between the museum and the local schools is the type of partnership school districts nationwide are trying to replicate. As head of the new STEM department in the Evanston/Skoki School District in Illinois, Jesch Reyes came to the summit looking for ideas.

“We need to figure out our vision in implementing NGSS to its fullest,”said Reyes. “We have to think less about what we should do right now at this moment, and more about the overarching vision for the next three-to-five years and where we want this to land.”

Reyes might find it easier to hire STEM teachers in the years to come. The 100Kin10 network is growing and is currently on track to surpass its goal by the 2021 deadline.