Carl Robichaud, Program Officer in International Peace and Security, is traveling with a group of journalists as part of the International Reporting Project’s trip to Kazakhstan, getting a firsthand look at energy, environment, human rights and nuclear issues there. He will sending updates from the trip.

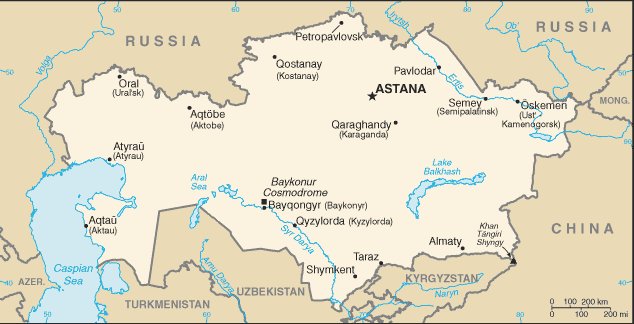

One of our first stops was in Semey, the largest community near the former Soviet nuclear test site of Semipalatinsk. There we visited a home for the elderly and disabled, many of whom had been exposed to the health consequences of nuclear testing. After a brief tour we were invited to observe the residents’ commemoration of Hiroshima Day, which involved local folk songs and a film on nuclear testing. Over the years the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have formed a special bond with residents of Semipalatinsk as a result of their shared history as innocent victims of war.

We heard stories from several residents who had lived in villages near the zone of maximum risk around the site. One woman recounted how, during one test when she was a child, everyone in her school was told to exit the building and lie down in the adjacent field. Presumably this was a precaution to avoid damage from structural collapse or shattered glass, which these tests regularly caused. But leaving the building also exposed the children to an increased dose of radiation. Others recounted witnessing the mounting evidence of illness and suffering caused by test radiation, even as Soviet officials prevaricated about the danger.

The Soviets conducted 456 nuclear tests at Semipalatinsk from 1949 until 1989. The local population knew of the test site, but state authorities kept them in the dark about the extent of their radiation exposure and the potential health consequences. The full details only came to light when the site closed with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, but one study by Kazakh and Japanese doctors concluded the population near the site received more than 500 millisieverts of radiation in one exposure. People in one village may have received a does of up to 1,400 millisieverts in 1949. (Nuclear industry workers today are only allowed 20 millisieverts per year).

It is extremely difficult to assess the full human cost of these tests. The health effects of radiation remain subject to fierce debate, and Soviet records from the era remain spotty. While it is virtually impossible to pin any particular illness to radiation exposure, scientists have linked higher rates of certain cancers, thyroid abnormalities, and heart diseases to post-irradiation effects. We were told by one scientist that cancer rates in the region were 2.5 times the national average, though there are other environmental conditions that may contribute to these levels.

Before we left, we were embraced by the residents and each presented with a paper crane. The crane echoes the story of Sadako Sasaki, a young girl exposed to the Hiroshima bomb who is remembered for making a thousand origami cranes before her death from leukemia.

The residents of this home for the elderly in Semey are among the last living survivors of nuclear testing, and a living monument to a tragic era that is slipping from memory. There are similar victims of atmospheric testing by other nuclear weapon states, including the United States. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the signature of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which banned atmospheric testing between the United States and Russia. Since then we have strengthened the global norm against nuclear testing, but the treaty that would ban all testing, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, remains stalled in Congress. It is my hope that we will see a ban to all nuclear testing before the last witnesses of this tragic chapter perish from the earth.

- Press Releases