Community College Students Find Strength in Numbers

Taylor Rountree took a year and a half to snag a spot in Yevgeniy Milman’s alternative developmental, or remedial, math class at New York City’s Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC). The 21-year-old had already withdrawn from the regular developmental education course—twice—because she was failing and decided she’d rather get out than get an “F” on her transcript.

Rountree found Milman on Rate My Professors, an independent website where students grade their professors on helpfulness, clarity, and easiness. “He was the top-rated math professor in our school, so I hunted him down like a hound to have him,” joked Rountree. “Finally, this semester I got lucky.” The waiting paid off. Standing outside room S741 on the main campus, which stretches along the Hudson River just blocks from City Hall and Ground Zero, Rountree smiled modestly and said she is not just passing the class; for the first time, she feels smart.

It’s easy to see why there’s a waiting list for Milman’s class. He’s calm, patient, and has a quirky sense of humor. He started the class with a warning—“Algebra coming in!”—followed by reassurance: “It’s not necessarily going to be anything bad because algebra is not a bad word; it’s just something that can be useful in certain situations.” Ignoring the moaning, Milman explained that for the next problem they would be figuring out how long someone who has had a few drinks should wait before legally and safely getting behind the wheel of a car. The students perked up. This they could relate to.

“The legal limit is this much in three gallons of blood,” Milman told his class, holding his thumb and forefinger about an inch apart to illustrate the tiny amount. A smattering of shocked murmurs erupted from around the classroom; it was much less alcohol than the students expected. Milman is attentive as he moves from group to group answering questions and trying to make sure every student understands the problem and what they’re being asked to do. When someone is struggling, he pulls up a chair and works one-on-one. When he senses broad confusion or misunderstanding, Milman stops everyone, goes to the blackboard, and reviews the lesson, then continues his rounds.

“I like that he thoroughly explains everything in real-world terms,” said 19-year-old Ciara Gipson, wearing jeans, a green T-shirt, and a serious expression. “It’s not just math and formulas and stuff, we have the opportunity to work it out on our own first before the professor explains it to us. Then we work it out together as a class and figure out what we did right and what we did wrong, instead of the professor just giving us the answers right off the bat.” Gipson said math was a difficult subject for her in high school and that’s how she wound up taking a remedial course. But after nearly a year in Milman’s class, she has experienced that “click,” when everything starts to make sense. That was remarkably clear when Milman asked Gipson to share the process she used to get a correct answer.

Over the next minute or so, the first-time college student began speaking in words that would send math phobics—which Gipson admits she used to be—cowering under their desks. She substituted a fraction in place of blood-alcohol level, subtracting another number, divided that by something else, and arrived at the wait time to take the wheel. “Absolutely!” praised Milman, beaming, “that’s absolutely correct.”

The program that boosted Gipson’s confidence and restored Rountree’s self-worth is part of the nationwide Community College Pathways initiative—two revamped remedial math courses created with Carnegie Corporation support and with liberal arts majors in mind. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (CFAT) developed the two courses, Statway (focused on statistics) and Quantway (focused on quantitative reasoning), which aim to move students more quickly into college-level math through an innovative approach that includes building lessons around real-life situations and having students work together in groups to figure out the answers.

What students learn will have “relevance, value, and purpose,” explained CFAT President Anthony Bryk, applicable to all sorts of daily decisions and current events, from calculating how long it takes for alcohol to dissipate, to making sense of political polls, to shopping for a mortgage. CFAT published a workbook for Quantway filled with everyday scenarios to keep students engaged in problem solving. A section on linear models, which can be used to chart the rate of change or to compare rates, uses cell phone plans as an illustration. Students are given prices for a two-year, flat-rate contract and a price-per-minute plan, and have to figure out which is the better deal, then graph their answer. M&M’s candy is the sweet spot in a Statway lesson on distribution of sample proportions. Each student receives a random sample of 25 M&M’s and plots the proportion of blue candies. Using everybody’s results, they have to figure out the best estimate for the proportion of all M&M’s everywhere that are blue.

The Heart of the Problem

Math problems based on real-world experience can make that subject less intimidating. But fear of math isn’t the only obstacle keeping community college students from reaching their goals. Simply transforming the content and structure of remedial courses won’t counteract years of negative messages many students received about their value, abilities, and future potential. At the heart of the problem are years spent in inadequate schools in impoverished neighborhoods that take their toll on student potential. Lawsuits such as Williams v. California, a seminal court case settled in 2004, rendered vivid images of low-income students stuck in elementary and secondary schools with crumbling plaster, broken bathrooms, insufficient textbooks, and a revolving door of substitute teachers.

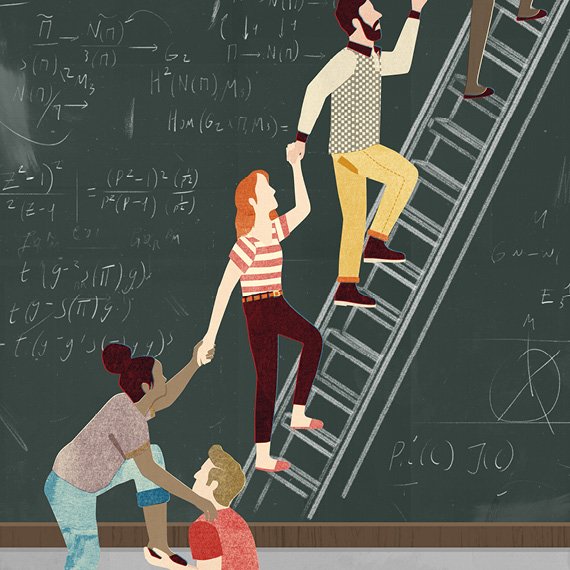

Even students tenacious enough to overcome those inequities and attend college face other hurdles. On average, 60 percent of entering community college students will be referred to developmental math because they don’t score high enough on the college’s placement exam. Of those, only 20 percent will advance to college-level math, which is the ticket to transfer to a four-year college or to earn an associate’s degree. No wonder students feel like interlopers who aren’t worthy enough or, as in Taylor Rountree’s case, smart enough to have a seat at the higher education table. Being told they have to take remedial math, even if it’s new and improved, risks reinforcing those beliefs.

“These are students who traditionally have not done well in math,” said Bryk. “They don’t see the relevance and purpose. They’ve come to think about themselves as not good at this. And if we’re actually going to figure out a way to sustain their active engagement in this work, we have to address these issues about motivation, given everything that the educational system prior to this point has signaled to them.”

The Pathways team at CFAT spent a lot of time reading and talking and thinking about how to address this challenge. They immersed themselves in research around social and psychological connections to learning, focusing on the work of renowned Stanford University psychology professor Carol Dweck, best known for studying growth mindset. Dweck and her team conducted a series of experiments with elementary school students and found that those who believed they weren’t smart and would never improve—described as having a fixed mindset—could change that self-perception by learning study skills, being told that they had the ability to succeed, and getting encouragement to keep trying and pushing ahead even if they failed now and again.

CFAT staff and Pathways faculty expanded Dweck’s idea into what they call “productive persistence”: essentially a set of skills, strategies, and mindsets that disadvantaged children and teenagers can use to improve their study habits, motivation, self-regulation, and tenacity. These motivational tools and habits of mind were embedded into the teaching, training, and structure of Statway and Quantway.

At American River College in Sacramento, California, Statway Professor Michelle Brock starts every class with a request intended to create a growth-mindset culture. Right after walking in the door and saying “hello,” before she’s pulled out the class materials from her rolling backpack, Brock glances at the handful of empty chairs and asks her students to get on their cell phones. “If you look around and see that somebody is not here, can you text them real quick to find out where they are?”

Brock’s class meets 3 hours a day, four days a week. Missing even one session could be hard to make up. But that’s not the only reason for the calls. “That’s reminding them they’re important here; you’re an important part of this class,” said Brock later that morning in her office. “One of the things researchers found that can affect a student’s success in a class can be whether or not they feel that they belong in college.”

Another critical piece of the process is group work. After reviewing their homework, the 26 students break

into the same groups they’ve been in all semester, scooch their desks into clusters, and turn on their graphing calculators. The group model works on multiple levels. “There’s a little bit of a family thing, a little bit of the banter that goes on between students,” observed Brock. “They’re comfortable with each and with the faculty.” Sometimes too comfortable.

“Mrs. B!” called out student James Dorris. She looked over but didn’t respond. Dorris tried again.

“She’s ignoring me now. I’ve used up my two Mrs. B’s,” he said to no one in particular, chuckling.

His assessment isn’t too far off base. After class, Brock explains that she intentionally doesn’t step in right away because the Statway method isn’t about handing out equations and having students fill in the blanks. It’s designed for students to work through the problems individually, share their answers within their groups, and work together to help classmates having difficulty. The bottom line is that they should try to work through the problems themselves before giving up and asking for the answer, and Dorris gave up too soon.

Triple the Success in Half the Time

At BMCC, nearly 80 percent of all first-time freshmen place into developmental math, and less than 30 percent pass the traditional version of the course, according to a 2014 report to the regional accreditation commission. But for students enrolled in Quantway, results are almost flipped—about 60 percent of them pass. Some community colleges have two, three, even four levels of remedial classes that don’t count toward graduation, could take two years to complete in the best of circumstances, require expensive books, and cost the same as any other class. The Community College Research Center (CCRC), located in Teachers College at Columbia University, found that just 10 percent of students who place three semesters below college math make it to the next remedial level. Typically, they run out of time, money, and motivation.

“Math kept me here two years longer than I should have been,” grumbled Debbie Huffman, who hopes to graduate this year from American River College and then transfer to nearby Sacramento State University. She was accepted into the anthropology department, pending a passing grade in this class. Huffman is 57 years old and impatient to finally earn a degree now that she’s in college. But everything she learned in high school algebra was long gone by the time she got here. “I was completely stumped, I could not do it,” recalled Huffman of her two failed attempts at pre-algebra.

Then she heard about Statway. The two-semester course combines three redesigned math classes—two remedial and one college-level statistics. She passed the first semester, but the second half is giving her trouble. “This semester is a real struggle for me,” conceded Huffman. She had just given her eraser a workout on a task that called for determining confidence intervals and calculating margins of error; in this case, determining the accuracy of a measurement, such as a political poll. For Huffman and other students who find themselves on shaky ground, Statway and Quantway are undergirded with supports. Tutoring is available and professors hold and keep office hours.

When CFAT started digging into problems at community colleges back in 2008, they found that high failure rates in developmental education were the “single biggest impediment” to student success, said Bryk. “They can complete everything else, but if they don’t get through that, all opportunities are blocked. They can’t transfer to four-year institutions and they can’t qualify for a number of different technical and occupational certification programs,” said Bryk. “This was a real high-leverage problem to solve.”

It’s not only struggling students who suffer the consequences. By 2020, just five years from now, 65 percent of all new job openings will require some postsecondary education. But the United States is looking at a shortfall of five million qualified workers. That gap can’t be closed without improving the odds for the 7.5 million students enrolled in degree or certificate programs at the nation’s more than 1,100 community colleges. They make up 42 percent of all undergraduates attending public and private nonprofit colleges, according to the latest figures from the National Center for Education Statistics.

Community colleges are also pivotal to advancing social and economic mobility. Forty-four percent of high school students with family incomes below $25,000 choose to attend community colleges after graduation. These institutions are also the top college choice for more than half of all Native American, Hispanic, and Black students. “This is really a central institution in our educational system,” said Bryk. “Yet community colleges are perceived as a lower tier of the [higher education] system in the United States.”

CFAT decided to take on this problem, and started the Pathways initiative as a pilot program. They invited the 26 community colleges within its national network to participate, assembling a team of math faculty from those campuses to take the lead. When American River’s Brock received the email, she was elated. “I went to the dean and said, ‘this is what I need to be doing.’” She had been discouraged by the high failure rate in remedial classes and the lack of any effort to address the problem. “We really did need to do something different; we couldn’t keep doing the same thing and expecting different results,” said Brock, referencing the definition of insanity.

She became a charter member of CFAT’s Pathways team. They spent the first year reviewing research, meeting with experts, designing the courses, writing curriculum, testing out lessons on their students, and tweaking them before the actual launch. Four years into the program, 80 percent of Statway students at American River College are completing the full yearlong course, compared to about 15 percent in the traditional course, said Brock. An analysis of all 18 community colleges in the initial Statway pilot found that 51 percent of the 1,077 students enrolled in the course in 2011 (the first year it was offered) completed it and earned college credit in one year, compared to 15 percent of students in the regular sequence earning college credit after two years.

At latest count, 49 colleges in 14 states are participating in Statway or Quantway, enrolling nearly 18,000 students since the Pathways initiative began. “Our tagline for Statway is ‘triple the success in half the time,’” remarked Heather Hough, an analyst at CFAT. “And it’s been true every single year even as we’ve added more colleges.” As a proven success, CFAT’s Pathways program has broad support in the field and is scaling up the program—which will again be funded by Carnegie Corporation.

One Size Won’t Fit All

While Pathways has been extremely successful for these students, up until now it did not deliver all the necessary algebra and precalculus content to enable students to take math courses in STEM majors or other programs requiring similar math preparation. But faculty from six colleges have been working together to build bridge courseware to take students from Statway and Quantway to precalculus. During 2014-15 the faculty developed a complete set of materials and pilot tested elements of them in their existing classes. The resulting curricula have now been shared network wide. Colleges can now make Statway and Quantway available to significantly more students, as the bridge option has expanded the number of majors for which the Pathways programs are appropriate.

The campaign to reinvent remedial math doesn’t end with Statway and Quantway. A two-year-old program also supported by Carnegie Corporation, the New Mathways Project at the University of Texas’s Charles A. Dana Center (a joint enterprise with the Texas Association of Community Colleges), offers a wide selection of alternative developmental education courses, each one fine-tuned to align more closely with a different major. Philip Uri Treisman, founder and executive director of the Dana Center, was part of the CFAT team that shaped the Pathways initiative. Groundbreaking research he conducted as a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, in the mid-1970s had given Treisman a valuable perspective on what it takes for students to succeed. That insight found its way into both programs.

As a student of math and education, he was interested in the factors that support high achievement among minority students in mathematics. In particular, he wanted to understand why African American students who were at the top of their high school classes did so much worse in freshman calculus at Berkeley than their Chinese American classmates. Treisman found that, beginning on the first day of class, the Chinese American students organized academically focused social groups.

By contrast, the African American students, accustomed to being among a small elite band of high achievers in high school, isolated themselves academically and kept their social lives and school lives separate. These observations led Treisman to establish the Mathematics Workshop Program, small science and math working groups for Black and Latino students.

Treisman’s early research found its way into the New Mathways Project currently being implemented in community colleges throughout Texas, especially in its use of approaches that help students develop skills as learners. Mathways students take a semester-long, for-credit course designed to help them develop the strategies and persistence necessary to succeed in college (particularly in mathematics courses) and in their careers and life. Mathways offers multiple course options with mathematics content aligned to specific fields of study. Acceleration allows students to complete a college-level math course quickly; and curriculum design and pedagogy are based on proven practice.

Recognizing that no one or two models can work for all students, CFAT is also exploring new alternatives. American River College student Kia Elliott fears that the Statway class she’s enrolled in is her last chance, but she’s not thriving here any more than she was in the college-level Algebra II. Elliott said the problem with Statway is that she’s not good at teaching herself and needs more direct instruction from the professor. “I think the teacher needs to teach more. A lot of students who come to this class, it’s the last resort that we have and a lot of us can’t teach ourselves,” said Elliott.

The widely varying needs of their students have led community colleges to try many different models of developmental education over the past decade with differing degrees of success. Through its NextDev Challenge project, the Denver-based Education Commission of the States has been following the trends and outcomes. One example, the GetREAL program at Berkshire Community College in Massachusetts, boosted pass rates in math from 39 percent to nearly 67 percent by working closely with students to make sure they take advantage of all the academic resources available to them and by helping them to manage the personal and social demands that can be distracting for first-year students. Virginia and North Carolina are leading the way in using instructional modules, which break out the individual competencies, such as fractions, into shorter one-credit units.

CCRC at Teachers College has received a number of grants to study reforms in developmental education, but most of the programs are still too new to generate the type of results needed to consider broad expansions. “It’s likely that certain approaches may work better for certain students, depending on their developmental need or their intended program of study,” said Nicole Edgecombe, senior research associate at CCRC. Still, she added, the early returns on Statway and Quantway show “some very promising short-term outcomes.”

For now, the biggest challenge with expanding Pathways even more is “getting math people interested in doing this,” suggested Michael George, a mathematics professor who teaches along with Milman at BMCC, and who has been part of the Pathways program from the beginning. For starters, he said, it requires a very different teaching style than most mathematicians are comfortable with. “There’s an inherently more informal relationship that develops between the students and the faculty in these Quantway classes,” explained George. Most traditional math teachers are used to being treated with great deference and respect, he said, but Quantway requires more of a coach than a professor, which is one of the reasons it’s hard to recruit faculty to teach in this program.

The preparation is more time consuming, said Brock from American River, and it needs a different kind of energy. Sometimes it’s hard to convince faculty members to take that on. Brock and the other early adopters have shifted their roles from developers and testers to mentors for colleagues across the country who are new to the program.

An ongoing organizational barrier that receives a lot of attention is the lack of alignment between public colleges and universities, even those in the same state. A student may earn an “A” in Statway, but that’s moot if the local four-year state university won’t accept the credits. Sometimes it’s a bureaucratic tangle, but more often it’s a philosophical debate over how much and what kind of math college students should be required to know. One side contends that students who aren’t majoring in a field that requires algebra or calculus should be allowed to take a math class that will be useful in their liberal arts career. Critics of that perspective maintain that without an agreed upon set of universal requirements, the value of a college degree is diminished. As Bryk pointed out, Statway and Quantway were designed as a deliberate challenge to that point of view.

The good news is, the mathematics community is increasingly recognizing and advocating for the need for differentiated courses for students based on their major and, relatedly, a need for greater emphasis on quantitative reasoning and statistics skills. Recently the University of California granted permanent transfer approval for Statway, another significant indicator. This is evidence of an ongoing evolution over the five years of Statway’s development. Although challenges remain, the hope is that the California State University system will also grant permanent transfer approval as will the University of Washington, both of which are up for consideration in the coming months and years.

Those who, like Professor George of BMCC, consider the Pathways approach to be the best way forward, contend that the old standards don’t meet the real needs of today’s community college students. In contrast, Pathways can help large numbers of students in multiple contexts gain essential mathematics skills to not only achieve their academic goals but to solve problems and improve their lives—all with the aid of clear quantitative and mathematical thinking. Consequently, “For me,” George says emphatically, “there’s no going back.”

Kathryn Baron is a California-based reporter. She has been writing about education for more than 20 years in newspapers and magazines, online, and for public radio.

- Education